Cross-Border Restructuring: A Strategic Response to Rising Geopolitical and Supply Chain Risks

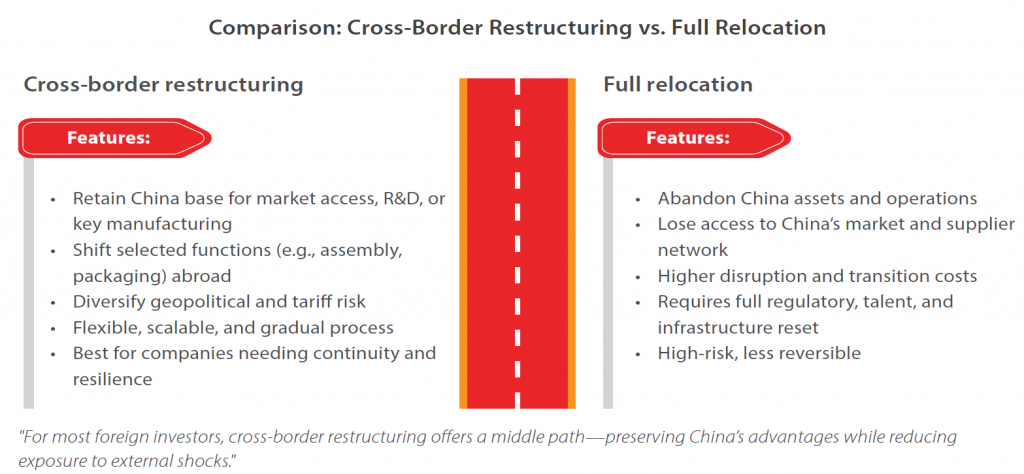

Cross-border restructuring is gaining traction among foreign investors in China as a response to rising geopolitical and supply chain risks. This article explains why this strategy is emerging as a more measured alternative to full relocation, helping companies maintain China operations while diversifying regionally.

In today’s volatile global environment, businesses with operations in China are facing intensifying pressures—from escalating US-China trade tensions to shifting tariff regimes, geopolitical fragmentation, and mounting calls for supply chain resilience. For many foreign investors, the question is no longer whether to adjust their supply chains, but how.

Yet while headlines often spotlight companies “leaving China,” the reality on the ground is more nuanced. For most multinationals, China remains indispensable—whether for its massive domestic consumer base, its sophisticated supplier ecosystem, or its vital role in global production networks. Exiting entirely would not only be disruptive but also economically unjustifiable.

In this context, cross-border restructuring is emerging as a viable, strategic middle path. It allows companies to reduce overdependence on a single jurisdiction, hedge geopolitical risk, and reconfigure operations across multiple countries, without abandoning the benefits of their China footprint.

This article explores why cross-border restructuring makes sense now, how it differs from full relocation, and how leading companies are using it to build a more resilient, future-ready supply chain.

The new normal: Geopolitical tensions and supply chain disruptions

Over the past decade, supply chains have moved from the background to the boardroom. What was once considered a technical or operational issue is now central to strategic decision-making, especially for foreign businesses operating in China.

At the heart of this shift is the evolving US-China relationship. Since 2018, successive waves of tariffs, export controls, and investment restrictions have disrupted trade flows and challenged long-standing operating models. The uncertainty is no longer temporary; it is structural.

And the challenges don’t stop at bilateral tensions. Businesses are also grappling with:

- Trade fragmentation: Rising use of local content rules, shifting origin standards, and diverging regulatory regimes.

- Geopolitical instability: Conflicts in Europe, the Red Sea, and other regions have further complicated global operations.

- Cost pressures: Rising labor, compliance, and energy costs in China—especially in coastal regions—are forcing a re-evaluation of total landed costs.

For companies that once built their global supply chains around cost efficiency and centralized production in China, these factors are prompting a reassessment. The question is no longer about the efficiency of China-only models—it’s about resilience, agility, and risk diversification.

Why leaving China entirely is not realistic

While many companies are exploring alternatives to reduce overexposure to geopolitical risks, a full exit from China remains largely impractical—and, for most, strategically unwise.

China is not just a manufacturing hub; it is a deeply integrated part of the global supply chain and an increasingly important end market. Several factors make a complete withdrawal from China infeasible for the majority of foreign-invested businesses:

- Unmatched industrial ecosystem: China’s supplier networks are highly specialized, vertically integrated, and often irreplaceable in the short to medium term. From components to tooling to testing, the ecosystem’s scale and depth are difficult to replicate elsewhere.

- Advanced infrastructure: World-class logistics, ports, road and rail networks, and reliable utilities enable efficiency and speed that many emerging alternatives still struggle to match.

- Strong R&D and talent base: In sectors like electronics, automotive, and green tech, China offers not only engineering talent but also growing innovation capabilities, making it a strategic base for more than just low-cost production.

- Massive domestic market: For many brands, China is no longer just a place to manufacture—it’s a core revenue driver. Scaling back too aggressively risks losing market access and competitive positioning.

- Regulatory and financial entanglements: Many foreign companies have sunk investments in land, factories, equipment, and local entities. Unwinding these assets is not only costly but can also trigger tax and legal complications.

Rather than abandoning China, many firms are seeking to rebalance, retaining key operations where China offers clear advantages, while gradually shifting parts of the supply chain elsewhere to spread risk. This is where cross-border restructuring becomes relevant—not as a retreat from China, but as a recalibration.

Cross-border restructuring: A pragmatic middle path

For companies caught between geopolitical risks and operational dependencies, cross-border restructuring offers a practical and flexible alternative. Rather than choosing between staying in China or leaving entirely, this strategy allows businesses to adapt their supply chains by reallocating certain functions—such as assembly, packaging, or low-value production—to other countries, while keeping strategic operations in China.

This approach, often described as “China + 1,” reflects a broader shift in mindset. It’s no longer about finding a single low-cost location to centralize everything. Instead, companies are building multi-jurisdictional supply chains that can absorb shocks, respond faster to policy changes, and meet the evolving demands of customers and regulators across regions.

What distinguishes cross-border restructuring from full relocation is its emphasis on balance and continuity. Businesses retain their foothold in China to serve the domestic market, maintain existing supplier relationships, or anchor R&D and high-tech functions. Meanwhile, they establish complementary operations in countries like Vietnam, India, Thailand, or Malaysia to diversify geopolitical exposure, reduce tariffs, and access regional trade benefits.

The benefits of this model are tangible. By splitting operations across borders, companies can better manage their original status for tariff purposes, qualify for different trade agreements, and mitigate the impact of country-specific export controls or restrictions. At the same time, they preserve the institutional knowledge, partnerships, and brand presence they’ve built in China over years or even decades.

Importantly, cross-border restructuring is not just a reactionary move. For forward-looking companies, it’s an opportunity to future-proof their supply chains, making them more resilient, cost-effective, and adaptable in an increasingly unpredictable global environment.

Early movers and lessons learned

Several multinational companies have already taken steps toward cross-border restructuring, offering useful insights into how this strategy works in practice. While their approaches vary by industry and scale, a common thread is the desire to mitigate risk without abandoning the advantages of a China presence.

In the electronics sector, for example, firms with deep manufacturing roots in southern China have started shifting final assembly operations to Southeast Asia—particularly Vietnam and Malaysia—where they can take advantage of favorable tariff treatment for exports to the United States and Europe. Core component manufacturing, R&D, and supplier coordination, however, often remain in China, where the industrial ecosystem is still unrivaled. This allows companies to keep their high-value processes centralized while using overseas facilities to navigate trade barriers more flexibly.

Apparel and consumer goods manufacturers, long drawn to China for its speed and reliability, have also begun diversifying. Some have moved parts of their production to Bangladesh or Indonesia, not only to reduce labor costs but also to respond to client demands for multi-origin sourcing strategies. These businesses often retain sourcing teams or regional headquarters in China to manage suppliers and maintain oversight.

In the pharmaceutical and life sciences industry, companies face additional regulatory complexity. Still, we are seeing examples of firms establishing secondary production sites in India or Singapore to ensure redundancy and avoid supply disruptions due to export controls or political sensitivities.

What these early movers reveal is that cross-border restructuring isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. It requires a tailored strategy based on product characteristics, supply chain complexity, cost structures, and regulatory environments. Some companies move quickly, launching pilot lines in new locations and scaling up after proof of concept. Others take a phased approach, shifting production step by step while continuously evaluating costs and operational performance.

A key lesson is timing and execution matter. Companies that acted early—before trade frictions escalated—were better positioned to cushion the impact and adjust smoothly. Those that delayed often faced rushed decisions and higher costs. The most successful transitions were led by firms that treated restructuring not as a crisis response, but as a long-term strategic adjustment.

Is it right for your business?

While cross-border restructuring offers compelling advantages, it’s not a universal solution. Whether this strategy is right for your business depends on a careful assessment of your operational footprint, exposure to geopolitical risks, and long-term strategic goals.

The first step is to identify where your supply chain is most vulnerable. Are specific products or components affected by tariffs or export controls? Do you rely heavily on a single production site or region that poses growing political or logistical risks? Understanding these pressure points will help define the scope of potential restructuring.

Next, consider what parts of your operations can realistically be relocated or duplicated abroad without sacrificing quality, compliance, or customer expectations. High-value functions like R&D or precision engineering may need to stay in China, while assembly or packaging can often be shifted elsewhere. For some businesses, the right answer may not involve physical relocation at all, but rather form partnerships or contract manufacturing arrangements in new markets to supplement existing capabilities.

It’s also essential to look beyond costs. While labor savings may be achievable in countries like Vietnam or India, companies must weigh these gains against potential challenges—such as infrastructure limitations, unfamiliar regulatory systems, or cultural and language barriers. In many cases, it’s not about where it’s cheapest to produce, but where you can build a stable, long-term presence that complements your existing operations.

Finally, leadership buy-in and internal alignment are crucial. Cross-border restructuring involves not only capital and compliance issues, but also people—managing talent transitions, rethinking workflows, and maintaining morale during periods of change. Companies that succeed are those that treat the restructuring process as an organizational transformation, not just a logistical shift.

Done right, cross-border restructuring offers more than just protection against short-term disruptions. It gives companies a stronger, more flexible foundation to grow in a world where agility and resilience are becoming just as important as efficiency.

This articles was originally published in our China Briefing Magazine issue titled: The China+ Strategy: Cross-Border Restructuring for Supply Chain Resilience.

About Us

China Briefing is one of five regional Asia Briefing publications, supported by Dezan Shira & Associates. For a complimentary subscription to China Briefing’s content products, please click here.

Dezan Shira & Associates assists foreign investors into China and has done so since 1992 through offices in Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Qingdao, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Suzhou, Guangzhou, Haikou, Zhongshan, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. We also have offices in Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Dubai (UAE) and partner firms assisting foreign investors in The Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Bangladesh, and Australia. For assistance in China, please contact the firm at china@dezshira.com or visit our website at www.dezshira.com.

- Previous Article How Are Tariffs Impacting Chinese Exports to the US?

- Next Article China-Malaysia Closer Economic Ties and Opportunities